NATURE & OUTDOORS

How Saudi is bringing Arabian leopards back from the brink of extinction

In 1996, it was estimated there were less than 200 Arabian leopards left in the wild. This is how Saudi is bringing them back to the wild...

Words by Sheila Russell

It is thought to have emerged from Africa 500,000 years ago and is a typical leopard in many respects, with pale golden fur and grey patterned rosettes or dots. Arabian Leopards are also described as being a little greyer in colour, blending in well with its environment. It is smaller than other species, with large males seldom reaching 30kg, half that of their African cousins.

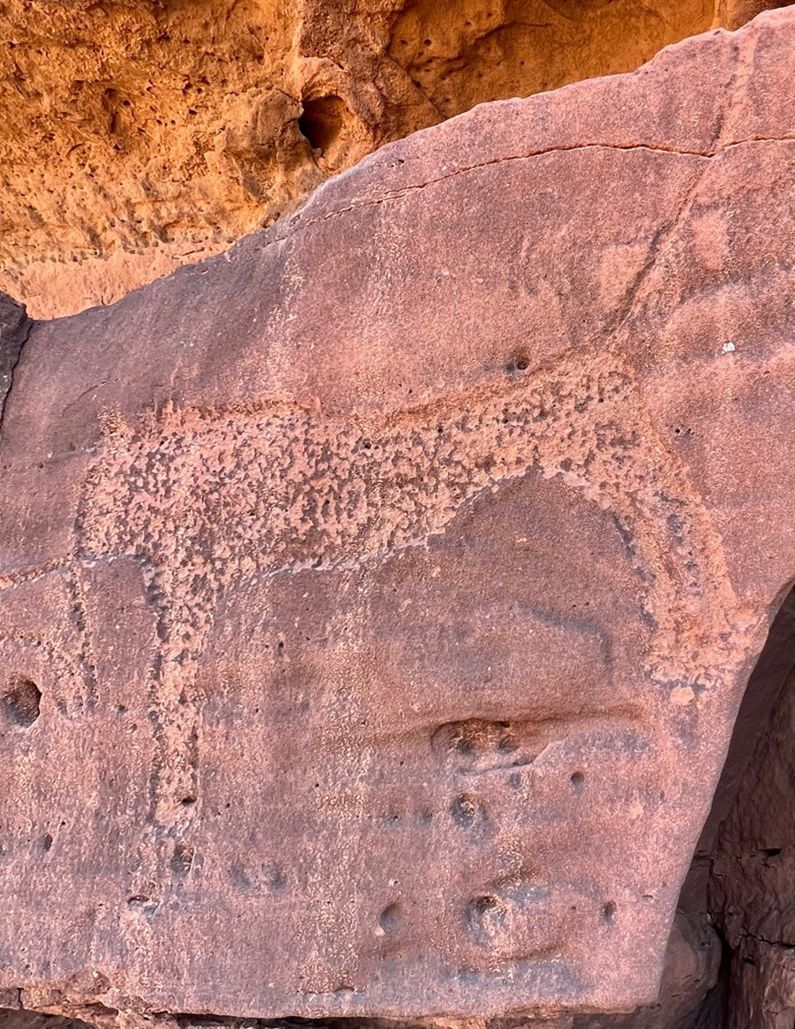

This elusive animal was common in Saudi in the past. The ancestors of today’s populations left traces in numerous petroglyphs and inscriptions on rock faces. The UNESCO World Heritage Site of Rock Art in the Hail region of Saudi is where you can see ancient depictions of these majestic animals. The site includes two components, Jabal Umm Sinman at Jubbah (90km northwest of the city of Hail) and two locations at Shuwaymis (250km south of Hail). Jabal Al-Manjor and Jabal Raat at Shuwaymis are an incredible pair of mountains sitting either side of a now dry valley. The large number of petroglyphs and inscriptions has been attributed to almost 10,000 years of human history containing the biggest and richest rock art complexes in the Kingdom of Saudi and the wider region. One magnificent example shows a leopard hunting, recognisable by its long tail, flat facial profile and stalking pose. More leopards are depicted here than any other area.

They are solitary predators and mostly prey on smaller animals than themselves. The rock art in Shuwaymis tells us a lot about their possible diet. Based on the animals identified, gazelles and small ibex fall within the range of possible prey. They wouldn’t always eat everything at once, storing carcasses in trees to protect themselves from competitors and scavengers.

Depictions of leopards can also be seen in the rock art of AlUla where a fabulous project brings high hopes for the future of this magnificent cat. In 2019 the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU) formed the Arabian Leopard Fund, an independent organisation that sponsors conservation initiatives across the region to secure a future of the species. The RCU is also working closely with Panthera (an internationally renowned organisation devoted to the conservation of the world’s wild cats) and IUCN on a re-introduction programme.

The RCU’s ambitious plan falls into 2 parts: a captive breeding programme and the establishment of a nature reserve to provide a home for these special animals.

The Prince Saud bin Faisal Wildlife Research Centre in Taif is home to the Arabian Leopard Breeding Programme. Here a multitude of experts are looking after everything from the leopards’ health to its welfare and diet, but the biggest issue is the genetic diversity of the population. They will work with other institutions that hold the same species; in the hope they can exchange animals in the future to increase the genetic pool. Announcements of the birth of new cubs is a joyous time, representing a new beacon of hope for the renewal of a subspecies on the brink of extinction. There are currently more than 16 animals ranging from two to 15 years and the hope is to increase this by 20 to 50 per cent over the next couple of years until they are at a level where reintroductions can take place. There is currently no date set for the release of the first leopards, but the RCU is working with both Panthera and the IUCN to develop protocols that will dictate how this is done.

Habitat restoration is the starting point of providing the best environment for the leopards and that’s exactly what’s happening at the Sharaan Nature Reserve in AlUla. Fencing off the 1,500 square kilometres of sprawling desert and valleys reduces the grazing pressure from livestock such as goats, sheep and camels, allowing the natural vegetation to recover. Native plant species including the low growing almost leafless desert shrub ‘remith’ (Haloxylon salicornicum), a large desert shrub ‘ratm’ (Retama raetam) and the aromatic herb Pulicaria incisa are all now thriving. Native Acacia trees have also been planted.

With the vegetation recovering the RCU has reintroduced Idmi and Rheem gazelles, Nubian ibex, Arabian oryx and red-necked ostriches. They are already starting to breed with young being spotted regularly by rangers. The RCU’s Ranger training programme takes enthusiastic individuals from local communities and trains them in a range of skills. Supporting anti-poaching efforts and carrying out scientific monitoring, along with engaging in education programmes with locals are some of the activities.

Bringing back Arabia’s big cat from the brink of extinction is a big ask, but there have been some great successes in the region the past. In the 1970’s the Arabian oryx disappeared from the wild, and the United Arab Emirates joined with Saudi in a captive breeding programme. Thanks to this initiative, the oryx was the world’s first species to go from being extinct in the wild, to being reclassified as ‘vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List. While big cat programmes are a little different to antelopes, the hopes are high and great progress has been made so far.

Visitors won’t be able to see Arabian Leopards for a couple of years yet, but they can visit the Sharaan Nature Reserve to take in the stunning scenery and experience the newly rewilded area for themselves. Pangaea Adventure Club run ‘Safari Sharaan’ activities where a professional guide takes groups into the reserve in an open top 4×4 vintage vehicle. There you can enjoy the unique rock shapes, plant diversity and rock carvings along with the chance of seeing an Arabian oryx or Nubian ibex.

Practical information

Visas

It’s surprisingly simple and easy to get an e-Visa for Saudi and the process is very similar to applying for an ESTA for the USA. Over 50 nationalities are eligible to apply for an e-Visa, including people from the UK and USA, with it costing (at the time of writing) 535 Saudi riyals (about £115 or US$143). Applications are swift and nearly all applicants will receive a response within three working days – most within 24 hours. To apply for your Saudi e-Visa, visit the official Saudi Tourism Authority website. If you’re from the USA, UK or the Schengen Area, you can also apply for a visa on arrival into Saudi. It’s slightly cheaper than an e-Visa, too, at SAR480 (about £102 or US$128).

Getting there & around

Local customs

To really embrace Saudi life and pay respect towards its traditions, there are a few local customs you should abide when travelling around the country. Both men and women should wear clothing that covers their elbows and below their knees when out in public. If you’re heading to the coast, it’s still expected you dress modestly. When meeting and greeting locals, whether it’s a market stallholder or a private guide, say hello with ‘salam alaykum’, which means ‘peace be upon you’, as well as offering a handshake.

Weather

You might think it’s hot all year round in Saudi but it’s a little more nuanced than that. The best time to visit the country is between October and March, when temperatures can dip as low as 20°C during the daytime, depending on where in the country you are, and rarely exceed 30°C. The summer months between June and September can get extremely hot, with temperatures often north of 40°C. But, do as the locals do and head out after dusk when it’s much cooler!

Is English spoken in Saudi?

Arabic is the official national language but English is widely spoken.

What is the currency of Saudi?

The currency of Saudi is the riyal, with the current rate (at the time of writing), around SAR4.76 to the UK£. You’ll need to pre-order money before you travel, as in the UK it’s not usually stocked in currency exchange booths.

What’s it like travelling in Saudi as a female?

We think you’d be surprised! To find out more, read our first-hand account on what it’s like to travel in Saudi.

What’s the time difference in Saudi?

Saudi follows Arabia Standard Time (GMT +3) all year round.