Tales from the

NAMIB DESERT

Through sharing their traditions and stories of survival with a small number of visitors, the drought-ravaged desert communities of Namibia’s remote north-west have found new ways to help preserve their cultures and this wild landscape in a changing world

Words and photographs by Karen Edwards

(Video: Shutterstock)

Clutching his walking pole with both hands behind his neck like a pensive snooker player, my guide Stanley Kasaona stopped to scan the ochre-coloured dunes of the Namib Desert.

“It’s as though we are on another planet, isn’t it?” he mused softly while staring off into the distance. The sands were speckled with occasional tufts of bushman grass and stretched for kilometres. Across the horizon, the setting sun had turned a cloudless blue sky into a hazy pastel pink. Everything was silent apart from the light whistle of the wind as it gently rearranged the golden granules around our feet.

Beneath us, on the banks of Namibia’s Kunene River, Serra Cafema – a Wilderness-owned, solar-powered luxury tented camp – glistened like a mirage under the waning light. Surrounded by wild tamarix ferns, emerald acacias and yellow-flowering nara bushes, it emerged like an oasis, shimmering beneath the Cafema mountains.

Retraining his deep-brown eyes to the steep descent in front of us, Stanley turned and offered me his hand: “Come on; this way.”

Within seconds, we were gliding at speed, our hands tightly clasped. My walking boots sliced through the powdery sand, even as I sank calf-deep into the dune with every step. We stopped to catch our breath at the base, laughing at the thrill of playfully slipping and skidding down this mammoth dune.

“Now we are friends,” Stanley exclaimed with a big smile.

Parts of the Namib Desert are among the driest places on Earth, which means the current droughts are making life even tougher for its communities (Alamy)

When the rains stopped

It was August and I had come to the Namib Desert, just a few kilometres from the Namibia-Angola border, for more than its dunes. Few make it to this far north-western corner of the country, which is home to a tapestry of communities living in an increasingly transforming and harsh environment. I wanted to see whether tourism was helping the region’s remotest villages to conserve this ancient land, despite the toughest of conditions.

The Namib Desert sprawls for more than 80,000 sq km, stretching the Atlantic coastline from southern Angola to north-western South Africa, and it is one of the oldest deserts on Earth. With an estimated annual rainfall of less than 10mm, it is also thought to be among the driest. As a result, life in this region relies on water from the perennial Kunene River, which slithers the foothills of the Cafema mountains, creating a natural border between Namibia and Angola.

Stanley explained to me that the river was also why his ancestors, known as the Himba (OvaHimba) people – descendants of the Bantu who originated from West and Central Africa – chose this region to call home.

“During the 1980s and ’90s, a severe drought led to the loss of 90% of the Himba’s livestock”

“Those that stayed around the Kunene survived,” he said. “Their families are still here today. The river is a source for life.”

Mostly living as semi-nomadic livestock farmers, the Himba were once considered to be among the richest peoples in Africa, due to the number of livestock that they kept. Setting up temporary villages, Himba families would journey up to 60km a day in search of water and vegetation so their cattle, goats, sheep and chickens could graze.

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, however, a severe drought across the African continent led to the loss of an estimated 90% of the Himba’s livestock. Their people survived against the odds, and the herds increased again when the rains returned. But, since 2013, Namibia has faced recurring droughts again, with the government describing the current situation as ‘the most severe for 100 years’.

Families are, once again, losing a lot of livestock, and even the area’s hardened desert wildlife has almost disappeared as a result. Still, the Himba continue to survive, travelling as far as is required on a daily basis to find water and vegetation for grazing.

Hupize [right], one of Crocodile’s daughters, and her child

Meeting ‘Crocodile’

The next day began with Stanley excitedly handing me a helmet. Our morning activity? A crash course in quad biking, with training taking place on a makeshift course near to the camp. It took two circuits before I was declared ready for the dunes.

We made our way slowly along the sedimentary escarpment leading out of the camp before speeding into the hills. Up and down the golden pyramids we went, climbing and plunging, while carefully following a route that skimmed the dunes, keeping our impact as light as possible. Every moment offered a new perspective and an extraordinary view of a landscape few have the opportunity to see.

Occasionally, our path would run alongside fresh oryx tracks that vanished high into the hills. At one point, Stanley stopped to point out a horned adder curled up beneath a rock. I lost count of the amount of ‘wows’ I uttered as I paused to take yet another picture.

Coming to a halt on a small hill an hour later, we spotted a village. “This is Otapi, home to Crocodile, who is the wife of the Chief,” announced Stanley.

“How did she come to be called ‘Crocodile’?” I wondered out loud.

“She was attacked by one while collecting water for her family on the Angolan side of the Kunene,” he replied matter-of-factly.

The settlement was flanked by a circle of large stones. Inside, I counted at least eight dwellings. Stanley explained how each home was built by the women of the village using mopane-wood sticks and insulated with dried cow dung, which kept the houses cool in summer and warm in winter.

The Himba way of life has always been a humble one: the men and boys are predominantly herders, who ensure the sometimes hundreds-strong flocks are fed and watered. They often live away from home for weeks, if not months, on end. The women and girls run the village, fetching water from the river and keeping everyone fed, ensuring that the children grow up strong and healthy. Some grow their own crops – corn, pumpkins, tobacco, beans – in allotment-style spaces along the riverbank.

“Moro moro nwapenduka [Good morning],” said Crocodile, giving a warm smile. We shook hands – a sign of respect in Himba culture – then I joined her, cross-legged, on the sand.

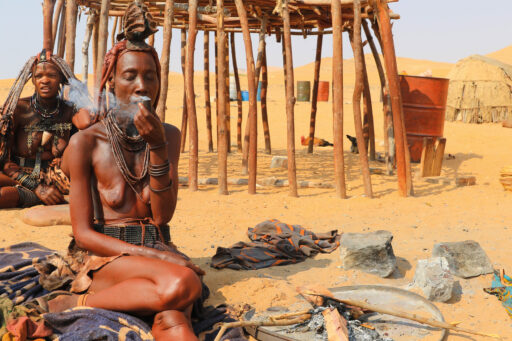

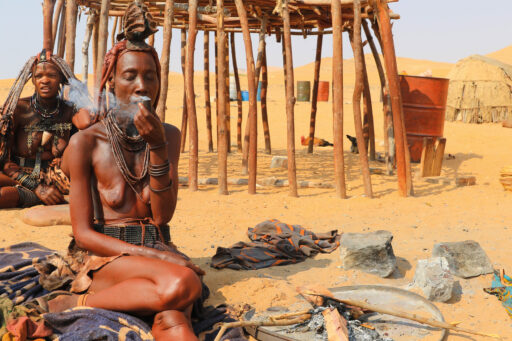

Crocodile was an elegant woman of around 55 years old; her chin was held high, her posture was confident. Her skirt, which was made from cowhide, had been a gift, presented to her during her coming-of-age ceremony many years ago. Around her neck she wore several beaded necklaces celebrating the nine occasions on which she had become a mother. The decorative cowhide on her head had been placed there by her father when she went through puberty, and her long fingers held an old clay pipe, stuffed with fresh tobacco, which she delicately smoked. Her sister, Mukjeimi, sat beading nearby while young children played all around.

“I grew up in Angola, where there were many civil wars,” Crocodile explained, answering my question on how she felt about visitors coming to her village. “When I crossed the river into Namibia, I started seeing tourists and their cameras for the first time. At first, I thought they were holding weapons. Then one of the Elders explained that these people were just visiting; that they only wanted to speak to me and take my picture. It was a completely different experience to the other side of the river.”

Life in the Namib desert isn’t easy, with droughts having taken their toll on the Himba people

The reptile that Crocodile takes her name from is common to the banks of the Kunene

Today, Crocodile and her family welcome guests with the hope that they can teach them about Himba traditions that have been practised for hundreds of years. They also make hand-crafted souvenirs for visitors, providing a small, but direct, revenue stream to the village.

Wilderness leases from the Himba the land on which the Serra Cafema camp is built. Additionally, the current Namibian government has recognised that conservation practices are most likely to succeed if Indigenous groups are able to maintain their land rights. The regulations around tourism have been formed around that idea. At my camp, a per-guest, per-night conservancy fee is required, which goes towards building local infrastructure, providing healthcare and mobile schools for the children. In turn, guests are invited to visit three nearby villages to interact and improve their understanding of Himba culture.

“I see tourism as an opportunity for us,” Crocodile said. “With whatever we earn from selling our handicrafts, I go to the small shop at the camp and buy porridge, and I feed my children. I also sometimes cross the river to Angola to buy jewellery for the girls. It helps our women appear more beautiful for our men. If I make enough money, I buy goats.”

Her words made me think of something Stanley had said earlier, when confirming that only one guest group could visit the community at a time. “We do not want to affect or change their way of life,” he told me. “We are there only to make life a little better.”

“We do not want to affect or change the Himba way of life… We’re only there to make it better”

Like the other women in the village, Crocodile’s skin and hair were covered in an auburn-coloured paste – a mixture of ochre rock pigment and a butterfat made from goat milk that is known as ‘otjize’. The lack of water in the desert means washing is impossible, so the women rub otjize into their skin as a cleanser. Together with a herbal smoke bath, using leaves taken from the commiphora tree, they are able to keep their skin clean, supple and smelling good. “For the men,” she added, roaring with laughter.

Despite the idea being frowned upon in Western cultures, polygamy is a natural way of life here, for the simple reason that the survival of the family bloodline is a priority if you’re living in the punishing, arid climes of the oldest desert on Earth. It is common for Himba men to have several wives, with the particular hope of producing as many males as possible.

Stanley helped me to understand this better: “The boys and men are vital for looking after the cattle,” he explained. “And having healthy cattle is how families build wealth and pass it on from generation to generation. It is how they survive.”

He paused thoughtfully, realising I needed to break even further away my Western perspective to fully comprehend what he was saying. “You know: in the Himba community there is no such thing as love,” he told me. “I never saw my father kissing my mother, or them holding hands while walking around together. The purpose of the family, the village, is to survive.”

Desert-adapted black rhino freely wander a 25,000 sq km area of Damaraland, though you can join tours tracking them on foot at Wilderness Desert Rhino Camp

A tale of coexistence

Leaving Otapi behind, I travelled south to Damaraland, a more rugged, sedimentary landscape. Here, against a backdrop of mountain peaks and ranges, Wilderness’ Damaraland Camp provides a laid-back and community-focused safari experience.

Even getting to the camp was a thrill. On the drive from the local airstrip, my guide Eno Handjaba and I spotted several springboks, two giraffes and a herd of ostrich.

Despite the dramatic change of scenery – and the seemingly abundant wildlife – Eno informed me that there hadn’t been a full rainy season here since 2018. The rivers had struggled to flow for more than a few days a year in all that time, meaning the wildlife and livestock were often lacking nutrients and a water supply. This story of perpetual drought sounded sadly familiar, and it has taken its toll on the Damara people, whose wealth – like the Himba’s – is rooted in their livestock.

In the small village of De Riet, siblings Rebecca and Laurence Adams also have to walk large distances during the day to source food and water for their goats and cattle. In addition to the drought, they face another of nature’s challenges: living side-by-side with the region’s desert-adapted wildlife. Elephant, lion and black rhino are just some of the species found in this area, making going in search of water a hazardous routine.

“It’s the elephants who cause the most damage, pulling out our crops,” remarked Laurence, referring to the community vegetable garden tucked behind the wooden houses. They also have a tendency to unearth and break into water pipes when the drought is at its worst. “It was once difficult, but we have learnt to live with it and have even considered new ways to look after ourselves.”

These new ways include sourcing income by engaging in the region’s tourism initiatives. De Riet villagers belong to the Torra Conservancy, which benefits from the per-person, per-night fees paid by guests of three Wilderness camps, including Damaraland Camp. These funds go primarily towards providing food and lodging for children attending the local school.

“Without that help, we’d have to fund the meals and hostel out of our own pockets,” Laurence said. “Very few people can afford to do that regularly, so we are very grateful.”

In addition to supporting the De Riet school, the funds from Damaraland Camp have launched several special projects for villagers, including a women’s sewing skills initiative and a tea station at the village information point. The only problem, said Laurence, was that some of the independent visitors who chose to self-drive could be a little careless in their approach.

“When they camp in our dry riverbeds, they don’t realise that they are ensuring no new vegetation can survive. Sometimes they drive past the village at 70kph, spreading dust in their wake. If I could ask anything of them, I would say: please visit the village; come and meet us – the Elders – and let us teach you about this environment. We can tell you about the elephants, lions, cheetahs; let us help to protect you and the animals. You can learn about our lives and our history.”

With a small ring in my pocket – sold to me by one of the Adams’ young great-grandchildren, who were manning the tiny tin shed of gifts outside the family house – I joined Eno, who insisted that we take the dusty track that overlooked the riverbed back to the camp.

“I have a feeling…” he said knowingly. Within minutes, we had rounded a corner to find a herd of female desert elephants, including a baby, sheltering from the sun under the foliage of an old acacia tree.

“They are cooling themselves,” whispered Eno as he turned off the engine of the safari truck. We watched on as the elephants rested, occasionally spraying a trunkful of dust over their bodies. Just a few metres away, the Adamses were tending to their vegetable garden before dusk.

The Vezema Village chief’s wife and her children

Make a difference while on safari

1. Pick a safari endorsed by the local villages

A reputable operator, based within a community-led conservancy, will put local needs first. This means your conservancy fee will go towards infrastructure and services. A little online research will tell you how an operator works with the conservancy leaders. If in doubt, ask them directly.

2. Meet the community Elders

Whether you go with a guide or self-drive, it is considered respectful to stop off at the local village to meet the Elders of the community, particularly in Namibia. Typically, this involves an introduction as well as a brief on the area from those who know it best. As well as being courteous, this is a great way to gain insight on where to find wildlife.

3. Carry local currency

If you’re considering buying souvenirs, do so at the local village. Bear in mind that card machines are a rare find – especially in areas without any access to electricity – so carry local currency or, at a push, bring US dollars to pay by cash.

4. Dress appropriately in local villages

Loose-fitting shirts, shorts and trousers are recommended for both sun-protection reasons and as respectable dress.

5. Ask about foundations

Many community-focused safari camps have foundations that fundraise for local projects, including female entrepreneurship programmes, building schools and health centres, and buying farm tools. Financial donations can make a great difference on a local level.

Opposite: The children of De Riet display the handicrafts that villagers sell to help fund the community as droughts take their toll on its traditional farming livelihood

The people of De Riet village have learnt to live in harmony with the elephants, who have been known to pull up crops and damage gardens, meaning the villagers have had to find other ways to support themselves, such as turning to cultural tourism

Need to know

When to go

Northern Namibia is a year-round destination that is rarely impacted by the country’s traditional rainy season (December to March). The shoulder seasons (May to June; September to October) are the best months to visit, before the northern hemisphere summer crowds arrive in July and August.

Getting there and around

Lufthansa and its partner Discover Airlines fly daily from London to Windhoek via Frankfurt from £816 return. Flights take from around 14 hours.

Internal flights are served by Wilderness Air, Wilderness’ domestic airline, which can be booked when making accommodation reservations at wildernessdestinations.com. Travellers can also self-drive to any Wilderness camps.

Where to stay

Room rates at Wilderness’ Serra Cafema camp cost from £684pp per night. Tents at Damaraland Camp begin at £387pp per night. All activities, including wildlife watching and community visits, are included in the price. To book, go to wildernessdestinations.com/africa/Namibia.

The trip

The author travelled with Wilderness on a tailor-made trip to north-west Namibia. The company runs safari camps and itineraries in Namibia, Botswana, Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe (wildernessdestinations.com).

Serra Cafema camp is set against the vast Hartmann’s Valley, sharing the space with the Himba – from whom Wilderness rent the land – with conservation and guest fees paid by visitors helping to support various community programmes