The forgotten

voyage

The discoveries made by the Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace should have ensured his place in history; now a thrilling voyage among the Indonesian islands and seas that inspired his revelations aims to right that wrong

Words Mark Stratton

Limestone islets scatter the Raja Ampat region (Alamy)

Circumnavigating islands and seas forgotten over time by all but those who live there, our vessel, Ombak Putih (White Wave), slipped by reefs of colourful corals and rainforests where birds-of-paradise kick up a fuss. I say ‘forgotten’ because Victorian Britain was once in the thrall of the eastern Dutch East Indies (now mostly Indonesia), thanks to the great naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who wrote an epic travelogue about his expedition there (1854–62) called The Malay Archipelago.

I had joined a 650-nautical-mile wildlife and science voyage from West Papua to the Maluku Islands (Moluccas) with the purpose of tracing the exploits of Wallace – a self-taught scientist from a humble Welsh background. Just as this region had settled into geographical anonymity amid Indonesia’s 17,000 islands, Wallace’s legacy had likewise faded. I wanted to learn more.

Sorong is a busy port and a gateway for ships en route to Raja Ampat (Alamy)

The Ombak Putih enters the waters of Raja Ampat, a region at the centre of Indonesia’s throughflow, the largest movement of water on the planet, whose constant flow of nutrients (from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean) is key to the incredible biodiversity you’ll find here (Mark Stratton)

Scientist and traveller

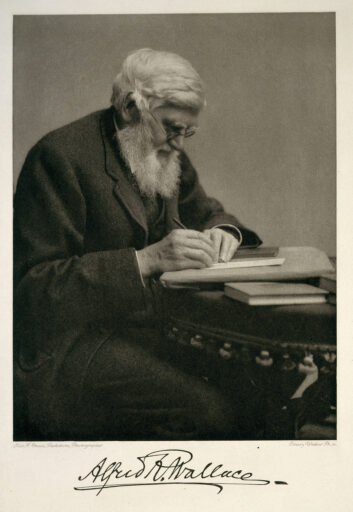

When he arrived in the Malay Peninsula region in 1854, Wallace was a little-known biologist; a rangy academic in his thirties who, for eight years, would roam the forests of what is now East Indonesia collecting specimens. Some 125,600 to be precise, spanning birds, butterflies and his beloved beetles. All were shipped back to London museums and private collectors; many were new to science.

It was in 1858 that Wallace had his eureka moment. Independently of Charles Darwin – a year and a half before Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published – Wallace theorised that natural selection was the mechanism driving evolutionary change. If he had published his theory immediately, his name, and not Darwin’s, would forever have been associated with this great discovery.

He also figured out the Wallace Line, a species barrier defined by plate tectonics, running longitudinally from Borneo to Sulawesi and between Bali and Lombok. My voyage sailed east of the line, in the biogeographical zone of Wallacea, where the fauna is Australasian (marsupials and birds-of-paradise), distinct from the western side’s Asiatic species, which include tigers and rhinos. I wondered why his scientific achievements had been largely forgotten since his death in 1913.

“When he died, Wallace was a very famous scientist and there were obituaries from across the world,” explained the voyage’s guest lecturer, Dr George Beccaloni, a chain-smoking evolutionary biologist and Wallace aficionado who has initiated a correspondence project to digitise the Victorian naturalist’s prolific letter writing. It was wise to whisper the word ‘Darwin’ around him. “After the First World War,” George continued, “Wallace’s fame diminished as scientists studying genetics recalled only Darwin’s contribution.”

It wasn’t just his scientific achievements that intrigued me during our 12-day Wallace-themed voyage. I wanted to explore the huge endemic biodiversity of East Indonesia that makes this region one of the most thrilling places on Earth to visit for lovers of wildlife.

Its maze of islands and archipelagos is best seen by boat, just as Wallace explored them. Crisscrossing this region, he moved around by Dutch mail-ship services or on outriggers called praus, on journeys that were often fraught. His writings recount the threat of ‘cannibals’ and, on one occasion, rats eating his sails after he had run aground.

The twelve-cabin vessel Ombak Putih was stylish and robust by comparison. The vessel’s seven sails rose above three decks of polished teak (it was strictly barefoot only) and the crew aboard were all Indonesian. I had a small bunked cabin near the bow that curved like a sultan’s slipper.

“Wooden pinisi boats have been sailed by our crew’s ancestors forever,” said Michael Travers of SeaTrek, who built Ombak Putih in 1998. “It’s a boat for Indonesian seas and weather – stable and strong.”

On departing Sorong to sail west into Raja Ampat, where the warm, shallow seas host magnificent coral reefs, circumstances forced a change in plans. Our onboard guide, Anastasia Louhenapessy (a mermaid in the water from Ambon Island), explained: “The last few months have seen significant coral bleaching, with sea temperatures up to 32ºC due to the latest El Niño event. It has left the corals as white as Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, especially on the most popular reefs around the Dampier Strait.”

Later in his life, Wallace warned of humankind’s negative environmental impact. I imagined him nodding an ‘I told you so’ at Anastasia’s briefing.

Changing course, we set sail for the Misool archipelago in southern Raja Ampat, where Anastasia said the throughflow impact of the warm Pacific water was lower. But before doing so, we had a rendezvous on Waigeo Island with two species of bird-of-paradise.

Raja Ampat’s reefs have thrived thanks to their isolation, though pollution, climate change and the damage from ship anchors are slowly taking their toll (Alamy)

A clownfish nestles among the tentacles of an anemone (Alamy)

Rainforests to reef

Wallace adored birds-of-paradise, and he made a tidy sum from sending specimens back to London that he’d blasted off their perches with buckshot. He catalogued 18 species, but 45 are known today.

On slippery laterite rainforest soils near Aframegata hamlet, we sought the red and Wilson’s varieties. George asked us to don demure colours, as oranges and reds disturb these birds – or perhaps colour-clash with their extravagant plumage.

“Wallace was the first to describe ‘lekking’,” said George, the word used to describe the male bird’s mating displays. Although he never actually saw either of these two species; just their skins.

Eat your heart out, Alfred; we saw both. The male red bird-of-paradise is rooster-sized and raspingly noisy. I craned my neck to see one lek on a high branch, its crimson plumage frilled out like a fancy Parisian parasol while its neck feathers oscillated iridescent green to blue in the crepuscular light.

Much easier to find – because it leks on the ground – was the Wilson’s bird-of-paradise. This blackbird-shaped endemic fastidiously hurled fallen leaves away from his showground, which looked no cleaner than when he’d started. Near speechless at his beauty, I’ll let Wallace describe him: ‘The upper mantle is sulphur-yellow… the wings pure red, the breast plumes dark green… the top of the head is bald, the bare skin of rich cobalt-blue.’ Most remarkable were the two tail wires that curled like a waxed moustache, refracting the sunlight to create a flickering neon effect as the bird hopped around.

The guide who took us onto his land to see them was Orgenes Mangaprou, a Papuan man who charged 300,000 rupiah (£15) per visitor. “I’m very happy to save the forest for birds because it’s good business for my family,” he told me.

While these extravagant colourations were thrilling, they were matched by the coral reefs we explored thereafter, during daily snorkels lasting one to two hours. We had sailed overnight, via the Kofiau Archipelago, to southern Raja Ampat to spend three days around Misool. It boasts the world’s greatest reefs, with more than 600 species of hard coral (75% of those known) and 1,300 varieties of fish forming a dazzling kaleidoscopic maelstrom.

Sadly for Wallace, his time here pre-dated snorkelling – he mentions corals in The Malay Archipelago less frequently than durian fruit. Yet I was sure he would have marvelled at the coral gardens shaped by grooved cerebellums, delicate gorgonian fans, wiggling soft tentacles and shamrock-green antlers.

I’ve spent time on the Red Sea and Great Barrier Reef, but neither came close to what I saw around Misool. At Sina, on one snorkel between limestone karst islands, we collectively counted over 100 fish species. I observed a hawksbill turtle levitate to the surface to gulp air, and I couldn’t help but think of Donald Trump as I watched clownfish, orange-faced with little pouty lips, vigorously defend their anemone homes. Make Anemones Great Again?

East of Misool, I saw blue sea stars the size of hubcaps; huge schools of fusilier fish with yellow crescentic tails; and lobsters, moray eels and lionfish playing peek-a-boo from rock crevices. Throughout, Anastasia located minuscule nudibranchs, multi-coloured and extravagantly decorated sea slugs with fanciful names such as the blue dragon.

Perhaps finest of all, I swam in a geologically uplifted saline lagoon full of jellyfish that had evolved to be stingless, due to a lack of predators. (I was sure Wallace would’ve figured out this adaptation.) Peachy-gold in colour, thousands bumped their transparent, otherworldly bodies together like slow-motion dodgems.

Misool is one of the four major islands (including Waigeo, Batanta and Salawati) within the 1,500-plus isles scattering Raja Ampat (Alamy)

The moluccas

My admiration for Wallace’s endurance grew throughout the trip. He often talked of being hungry, due to problems finding food, setting off on one journey with just a blackened chunk of turtle meat. I had few such concerns, but conditions were tricky at times. Tropical rain cascaded off our second deck canopy, where my ‘drying’ snorkelling clothing had surrendered to mustiness. Under titanium-dark skies, our voyage became more a survival of the sweatiest than the fittest. Wallace must have been Shackleton-hard with the neoprene attributes of Aquaman.

He also must have savoured, as I did, the licks of refreshing breezes and the thrill of watching waterspouts spinning off equatorial storms like Medusa’s locks. I felt he would’ve appreciated our academic endeavours too, pawing through fish identification guides before lunches and dinners. Maybe he had also tried kolak – a local dessert of sago pearls, bananas, brown sugar and coconut milk – which our chef prepared for us.

Before departing Misool, we called by Aduwei, a fishing village of 400 locals backed by primary rainforest. The villagers headed down their wooden jetty to greet us. Only the Ombak Putih calls here, twice each year.

“They are Melanesians – a mix of Papuans and people from other islands. But I cannot understand their language, so we communicate in Bahasa, which we learn in school,” said Anastasia. We watched them preparing sago palms into blocks heated over a wood fire.

“On our ID cards, we must state our religion – usually Christian or Islam – but most communities maintain their old spirit worship,” she continued. “In the Moluccas, we believe the frigatebird is a good spirit.”

It was a 13-hour overnight sail to our next stop, deep in the Moluccas. I had considered my Indonesian geography to be good until now. Like Wallace, who was armed with rudimentary maps, we entered little-visited waters, crossing that evening into the Halmahera Sea.

“Beyond Misool, you’ll hardly see any other boats,” foretold Anastasia.

We woke off the shore of Pisang Island, an extinct rainforested volcano midway across the sea. It wasn’t visited by Wallace but George was certain that there were new endemic species to be found there. In the afternoon, we blazed a small trail with a machete to the island’s summit. It was stultifyingly humid, our way snagged by trailing vines and barriers of buttressed roots.

“It’s a taste of what Wallace experienced collecting specimens,” said George. Around me, I sensed Wallace’s unquenchable curiosity at the prospect of finding species new to humankind. At one stage, a cockatoo squawked overhead. Might something similar have sparked his theory that Australasian species lie eastwards of his Wallace Line?

Beyond, we reached a chain of volcanic peaks in the Moluccas. These spice islands saw the Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch arrive in search of iniquitous trade deals and conquests, carting away barrels of the nutmeg and cloves that grow in abundance. Wallace arrived among this seascape of islands and small sultanates of waning power in 1858 and was captivated. ‘The Moluccas offer to the naturalist a very striking example of the luxuriance and beauty of animal life in the tropics,’ he wrote. But one particular bird and a butterfly sent him into raptures.

Pisang is a dream spot for divers and snorkellers, thanks to the island’s secluded waters, small population and magnificent jungle, which is ripe for exploration (Mark Stratton)

Wallace’s standardwing bird-of-paradise was first described in 1858 (Alamy)

Natural selection

On Bacan Island, it was dark when we began trekking into the hills at 4.30am. Our torchlight glanced upon a box turtle and coiled brown snake. Pausing near a lofty canopy tree, a silhouetted figure appeared on a lateral branch 30m above. Its call – more screeching clarion – woke the forest, and while I can’t pretend to have had a perfect view, the bird, like a vaudeville tease, slowly revealed its large red feet, a vivid blue cloak and a condor-like head. Most curious of all were the four erect wires emanating from the male’s back. When Wallace first saw them, he thought they resembled military standards.

We’d found Wallace’s standardwing bird-of-paradise.

“He was so excited to see it, he wrote it was the greatest discovery of his career, with natural selection coming in second,” said George.

A short hike away, amid nutmeg trees and coconuts ripening for copra, I met Mr Alisi. With a net, he swiped up a large male birdwing butterfly, its wingspan measuring just shy of 18cm, capturing it in the same way that Wallace would have done. To help protect this rainforest – especially with the pernicious rise of oil palm clearances – he farms this divine creature, selling some specimens to foreign collectors to make a little income.

Birdwings are the world’s largest butterflies. This one bore golden and orange segments and a sulphur-yellow abdomen. It is named Wallace’s golden birdwing, and its discovery overwhelmed its namesake: ‘My heart began to beat violently, the blood rushed to my head, and I felt much more like fainting than I have done when in apprehension of immediate death,’ he wrote, rather excitedly, upon capturing one.

The final day of the voyage felt spine-tinglingly momentous. We had sailed between two island volcanoes, Ternate and Tidore, to a broad mangrove-lined bay at Dodinga, on Halmahera Island, where George promised that we would see “one of the most important scientific locations in history”.

In February 1858, on a four-week field trip from his temporary home on Ternate, Wallace contracted malaria and was forced to recover in a thatched hut in Dodinga village, then a Dutch East Indies outpost. For years, he’d sought a scientific mechanism for evolutionary change, away from the orthodoxy of creationism. In his delirious state, the theory of natural selection by the survival of the fittest presented itself to him.

In haste, he drafted out his theory. But rather than publish it, he sent his ideas to Charles Darwin to canvas his thoughts. A startled Darwin had worked out this mechanism

20 years previously but had dallied over publishing. Now, a little-known collector (Wallace) had come to the same conclusions.

George thinks Wallace was cheated by London’s scientific establishment, of which Darwin was a stalwart. A joint publication by the two was released in July 1858, yet Wallace’s input had been published without his consent and Darwin was credited first. The experience, George insisted, had clearly jolted Darwin into finally writing and publishing On the Origin of Species in 1859.

After a short walk through banana plantations, I arrived near a mosque with an onion-shaped tin dome. Here I found a plaque and panel arranged by George that marked where Wallace had had his epiphany. As a rare visitor to Dodinga, I was joined by curious villagers.

In 1862, Wallace returned to Britain, via Singapore, where he wrote The Malay Archipelago. As I left behind Dodinga, I couldn’t help wondering how he’d have felt if he’d known that, despite theorising natural selection, he would be left to history’s footnotes.

I learnt that Wallace was never bitter about how events unfolded. Indeed, he respected Darwin and the two became friends. It had become clear to me by now that he should not solely be remembered for coming so close to scientific immortality but as one of history’s pioneering travellers. Throughout this sea voyage, I had experienced lands and seas of extraordinary biodiversity. I had shared Wallace’s enthusiasm for scientific discovery in a region every bit as fresh and relevant to travellers today as it was back in his era.

The Wilson’s bird-of-paradise is endemic to Waigeo (Alamy)

The goldenwing butterfly is only found east of the Wallace Line (Mark Stratton)

How to care for coral reefs as a traveller

Rising sea temperatures caused by the recent El Niño, allied with sewage pollution from dive liveaboards and resorts, have placed the Western Pacific’s Coral Triangle under duress. It’s easy to feel powerless: the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping sea temperatures below a 2ºC rise since pre-industrialisation is already being superseded. But, on a local level, we can make an impact by leaving behind healthy coral in our wake.

Avoid treading on any corals, as they are very fragile, and be sure to use reef-friendly sun protection cream when in the water. I have a light wetsuit (and swimming cap), leaving no exposed flesh, so I can avoid using sun protection. And don’t leave behind your plastic waste for it to be disposed of locally (some countries do so poorly); take it home with you.

Ask what your operator’s policy is on sewerage disposal. Accepted (yet not perfect) practice is to deposit it in the deep ocean, far from the reefs. If you’re land-based, ask whether your accommodation has any way of tackling effluence, such as a wastewater garden. And support the likes of Barefoot Conservation (barefootconservation.org) in helping Indonesian communities with their waste management.

Incredible corals in the waters off Pisang (Mark Stratton)

The plaque at Dodinga marks the spot where Wallace’s fever-induced epiphany enabled him to divine the secrets of natural selection (Mark Stratton)

Need to know

When to go

It’s sweaty year-round in Raja Ampat, with high humidity and temperatures of 25ºC to 32ºC. October to April is the best time to travel, despite it receiving the heaviest rainfall.

Getting there & around

Singapore Airlines (singaporeair.com) flies from London to Jakarta via Singapore. Connections to Sorong and Ternate, where the voyage begins and ends, can be found with Garuda Indonesia (garuda-indonesia.com). The flight time is about 23.5 hours.

Where to stay

In Sorong, the four-star Swiss Belhotel is arguably the finest stay in town. B&B doubles from £45pn (swiss-belhotel.com).

The trip

New Scientist discovery tours (newscientist.com/tours) offer a 13-day Alfred Russel Wallace expedition cruise in Indonesia on the Ombak Putih. Guests board in Sorong and sail across Raja Ampat to the Maluku Islands with guest lecturer Dr George Beccaloni. The trip costs US$13,999pp (£11,116), including all transfers, excursions, meals, snorkelling equipment and guiding. The next departure is 23 January 2026.

Scanning the trees for signs of life on Bacan Island (Mark Stratton)