Change is afoot as Albania comes to terms with its newfound popularity. But can community-based tourism save its wildlife, towns and shores from the masses?

How community experiences are changing the face of travel in Albania

Change is afoot as Albania comes to terms with its newfound popularity. But can community-based tourism save its wildlife, towns and shores from the masses?

Words Jessica Reid

Tirana’s Namazgah Mosque is the largest in the country (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Tirana’s Namazgah Mosque is the largest in the country (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

One of Tirana’s friendly locals (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

One of Tirana’s friendly locals (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

The fortified remains of Berat and its white-walled Ottoman houses (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

The fortified remains of Berat and its white-walled Ottoman houses (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Eva Rrasa swirled the grainy remains of my Turkish coffee around a dainty ceramic cup. She then poured out the last of the liquid into a saucer and observed the leftover granules clinging to the sides.

“You’re being followed by a man whose name begins with E,” she told me while holding my gaze. My eyes widened upon hearing the news, and she quickly moved to reassure me. “But don’t worry; he doesn’t want to cause you any harm. He’s just watching you from a distance.”

Together with her husband and children, Eva had welcomed me into her home in the rural village of Babunje, within western Albania’s Divjakë-Karavasta National Park. My visit – and impromptu coffee reading – was part of a community-based travel experience. By staying in the secret corners of Albania, I’d hoped to gain a deeper understanding of its traditional ways of life, while also making genuine connections and memories with the people who call this beautiful country home. The idea of a mystery man watching me from afar certainly wasn’t part of the plan.

The statue of Skanderbeg, who led the fight against the Ottomans in the 15th century, stands in his namesake square (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

The statue of Skanderbeg, who led the fight against the Ottomans in the 15th century, stands in his namesake square (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

The drive for community tourism experiences like this comes at an important time for Albania. The Balkan nation might have been closed off from the world during the 46 years it was under communist rule, but that ended in the early 1990s. A record-breaking 10 million people visited the country in 2023 – more than triple its entire population. Today, with the vast majority of visitors flocking to its Adriatic coastline for a budget-friendly beach break, concerns are growing for the impact this will have on coastal environments and communities.

Although Albania is eager to reap the economic rewards of tourism – evident in planned infrastructure projects that include roads, hotels and airports – the prevailing political mood now leans towards shifting the direction of its tourism. The new idea is to encourage travel that’s not all about sun, sand and sea, but about immersing yourself in the country’s little-visited communities, protected nature and unique culture and heritage. I was eager to see what early visitors to this new Albania could expect.

Tirana’s National History Museum on Skanderbeg Square has a tough but important exhibit on those who suffered under Albania’s communist rule (Alamy)

Tirana’s National History Museum on Skanderbeg Square has a tough but important exhibit on those who suffered under Albania’s communist rule (Alamy)

Inverting the pyramid

I began my journey in the mountain-enclosed capital of Tirana not looking to the country’s future, but at its recent past. During Albania’s time under Enver Hoxha’s long dictatorship (1941–85), many of the city’s churches and monasteries were torn down as atheism was forced on the population.

“Even religious names were banned – that’s why you will meet so many Elvises or Eltons. People were named after rock stars instead,” my local guide, Elton Caushi, explained as we arrived in the city centre. Born in the 1970s, Elton had lived through the hardships of communism, followed by the civil war and the Kosovo war of the 1990s. But over the past 25 years he had also seen his beloved country rise from the ashes.

Exploring the capital’s colourful architecture (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Exploring the capital’s colourful architecture (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Left in the Brutalist wake of communism was a city of unashamedly grey, Soviet-style structures. Yet, as Elton led me through the streets of Tirana’s little-visited Old Town, I began to notice the urban mood quickly shift, as brightly painted buildings and artistic murals took over.

“Tirana was becoming a city of concrete blocks. But our prime minister [Edi Rama] is a former arts professor and he brought colour back to our city,” Elton beamed proudly.

I could see Rama’s creative influence as we explored deeper into Tirana. Newly built high-rises took on unique shapes and styles, and many of the city’s bunkers (Hoxha ordered the construction of hundreds of thousands across Albania) have been repurposed into museums, such as the Bunk’Art gallery. The biggest shift came in the centre, where modern Skanderbeg Square is now the buzzing heart of a brave new capital.

The city has turned the Pyramid of Tirana – a vainglorious monument to a dictator – into a playful symbol of its future (Jessica Reid)

The city has turned the Pyramid of Tirana – a vainglorious monument to a dictator – into a playful symbol of its future (Jessica Reid)

But if there is one abiding symbol of this renewal, it’s the Pyramid of Tirana. Formerly a Brutalist monument and museum celebrating the life of Hoxha, for years it was left to rot. Now the 21m-high structure has been restored to a gleaming venue that locals can be proud of – and can even slide down parts of it.

“Although Tirana’s historic buildings have suffered, the architecture we have now is quirky and different,” Elton explained as we looked out at the city from the tip of the Pyramid. “We are a nation of big dreamers – we don’t want to be average.”

Flamingos hot-foot it through the shallow waters of Karavasta Lagoon (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Flamingos hot-foot it through the shallow waters of Karavasta Lagoon (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

A breath of fresh air

I had relished getting to know the fast-changing, modern capital, but I was looking forward to my first taste of rural Albania. As soon as I arrived at Divjakë-Karavasta National Park, a 90-minute drive from Tirana, I was immediately welcomed by John and Vlashi, two rescued pelicans who had made themselves at home next to the visitor centre within the park’s pine forests.

Divjakë-Karavasta is one of Europe’s most important habitats for the formerly endangered Dalmatian pelican, as well as being home to a further 260-plus species of bird. With help from the government, conservation efforts here have been ramping up in recent years, with its informative educational centre raising awareness of the fragile ecosystem, while park rangers now guard its wildlife against poachers. More recently, a wild bird rehabilitation centre was constructed, and it has already treated pelicans, herons and eagles since its opening in 2023.

Even Dalmatian pelicans suffered under communist rule, as large swaths of wetlands were drained in the 1950s and ’60s (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Even Dalmatian pelicans suffered under communist rule, as large swaths of wetlands were drained in the 1950s and ’60s (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

I was told by Ervin, one of the rangers, that pelicans could be found breeding on an island in the park between January and April. For the rest of the year, they tended to scatter across the region, so wild sightings were not guaranteed during our September visit. Nevertheless, I was still excited for what I’d find on the following morning’s sunrise birdwatching expedition.

After a 5am alarm call, I piled into the park’s new electric buggy, driven by Elton, who veered off-road to follow a bumpy dirt track across the coastal meadows. As daylight began to brighten the grasslands, I spied a wooden viewing platform that overlooked Karavasta Lagoon. Here we set up blankets and chairs for a picnic breakfast and pulled out our binoculars.

Sipping on coffee, I quietly yet gleefully observed egrets, kingfishers and flocks of flying flamingos. In the distance we could make out the shape of two pelicans standing stiffly to attention in the lagoon, the motionless water surrounding them burnished by the fiery orange sky reflected on the surface.

A stonemason’s work is never done (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

A stonemason’s work is never done (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

This magical morning geared me up for a 25km electric-bike ride to explore more of the national park’s woodlands, wetlands and sand dunes. Elton and I were on our way to the Rrasa family home, where we’d been invited to have a home-cooked lunch. Eva, her husband Adriatik and their children warmly greeted us with smiles at their front gate, despite us arriving later than expected.

As soon as I stepped onto their property, my eye was drawn to the stone carvings and sculptures scattering the decorative courtyard. Sheltered by a vine canopy, many depicted figures from the Byzantine empire that once ruled Albania. Some had been collected by Adriatik; most were chiselled by him and his eldest son, Euro, who had studied at the University of Arts in Tirana. My mind went back to the artsy capital and I mentally ticked off one more example of how things had transformed there for the better.

Ready for lunch, I followed the scent of homemade food into the family’s dining room. Eva had been cooking since 8am.

Never doubt the mystical powers of Turkish coffee (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Never doubt the mystical powers of Turkish coffee (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

“We have fertile land here, so everything that we need we can grow ourselves or get from our neighbours – our community has a good fraternity,” said Adriatik. I tucked into dishes of fresh chicken, duck, tomato and egg, and perhaps chugged down the wine a little too quickly. Adriatik smiled: “Next time you come, I’ll get the wine off my other neighbour – theirs is even better!”

Post-lunch, Eva put her coffee-reading skills to good use. She had taught herself, though it is a popular enough pastime in Albania, where every cup of coffee is a chance to divine a freshly brewed destiny. When it was time to leave, she pulled a pomegranate off a tree and handed it to me as a parting gift. My future was looking rosier already.

One of the more secluded spots near the busy beach town of Vlorë (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

One of the more secluded spots near the busy beach town of Vlorë (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Bay of plenty

Travelling south, our next stop came in the Bay of Vlorë, where I got to see the other side of tourism here. Its picturesque coastline – romantically dubbed the ‘Albanian Riviera’ – was filled with beach-loving tourists. Phalanxes of colourful sunbeds and parasols massed on the shoreline. And as we drove along the bypass above the city of Vlorë, I saw how the hotel tower blocks along the coast now obstructed the bay views of the old homes that lay helplessly in their shadow.

“We haven’t done everything right,” Elton sighed. He told me about the controversial airport being built near Vlorë, set to open in 2025. Albania is keen to have more visitors, though such things are often at the expense of attracting responsible tourists that care for the environment. I wasn’t sure this would help.

The bay is home to the National Marine Park of Karaburun-Sazan, which I learned more about down at the waterfront’s visitor centre, an important facility for educating travellers about the precious ecosystem here. I learnt that the waters hide a great variety of species and habitats: coral, seagrass beds, three species of sea turtle, common dolphins and even the rare Mediterranean monk seal.

One of the more peaceful areas in Vlore (Jessica Reid)

One of the more peaceful areas in Vlore (Jessica Reid)

It was then time to head into the bay to explore Karaburun Peninsula for myself on a boat tour. The highlight was a trip to the mystical Haxhi Ali cave, a huge sea grotto coated in stalactites that conceals azure waters so dazzling that I couldn’t resist diving in.

There’s no doubt that Vlorë’s natural beauty is staggering, but its ancient history is perhaps more so. The archaeological park of Orikum sits in the south-west corner of the bay. Located within an active military base, Elton managed to gain us access to the little-visited ruins that were a strategic port for Albania’s ruling empires across millennia.

The site was first developed by the Greeks in the 5th century BC, though it was later captured by Julius Caesar in 48 BC, during the Roman civil war, as he sought to defeat Pompey and take the republic in hand. Wandering through this history was thrilling, and I imagined a time when the fountains, churches and theatres – carved from local limestone rock – stood in place of these ruins. In the meantime, excavation work on the site continues, unveiling more stories and mysteries surrounding Albania’s history.

Boats wait to drift into Haxhi Ali, a karst sea cave that conceals gloriously azure waters within (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Boats wait to drift into Haxhi Ali, a karst sea cave that conceals gloriously azure waters within (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

As golden hour approached, Elton led me on a short stomp up the mountainside, as we followed a stoney path and then veered off track through the long grass and groves of oak trees. Soon, the homestead of shepherd Sofo and his wife, Dhurata, appeared in a clearing. Sofo encouraged us to join him as he put to bed his free-ranging goats before it got dark.

While he and his dog herded the animals into their pen for the night, I watched from the hillside with a glass of homemade cinnamon-and-honey-infused raki (brandy) in hand. In the distance, the Bay of Vlorë and the ghost village of Tragjas – bombed and abandoned during the Second World War – were illuminated by the fluorescent orange sunset. I wasn’t sure if it was the extraordinary landscape, the soothing sound of jingling goat bells or the warmth of the raki in my throat, but it was in this moment that I knew I was falling for Albania’s charms.

I returned to the farmhouse, where Sofo pulled out a wooden flute and serenaded us with a tuneful melody. Dhurata produced a sweet fried pastry and placed it in my hand.

Sampling home-cooked treats is a constant perk of spending time with locals like Dhurata (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Sampling home-cooked treats is a constant perk of spending time with locals like Dhurata (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

“It’s called petulla. I’ve made them in celebration of my niece being born in Germany. It’s an Albanian tradition,” she told me.

I was then directed to take a seat at the table as a mouthwatering supper was served. Consisting of stove-cooked burek bread (to be torn apart with our hands – “It’s disrespectful to cut with a knife,” I was told), fresh ricotta cheese and herb-infused potatoes, I was fascinated by the traditional techniques still being used to store and cook this produce.

I felt honoured that the couple not only shared their food, but gave me a glimpse of a more traditional Albanian lifestyle. Sure, the Vlorë coastline looks nice in a photo, but it was interacting with people like Sofo and Dhurata that stuck in my mind.

Berat is known as the ‘Town of a thousand windows’ (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Berat is known as the ‘Town of a thousand windows’ (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

A window on the world

The final stop on my trip was the historic centre of Berat. This fortified hilltop town, surrounded by the Tomorr Mountains, has been a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2008. This is largely due to the presence of a labyrinth of white-stone Ottoman architecture that winds through the city’s Mangalem Quarter and a 13th-century castle, known as Kala. But its origins are said to date back much further that its medieval fortifications.

Berat was founded as the ancient Greek polis of Antipatreia in 314 BC by Cassander, who was soon to be crowned the king of Macedon. There’s also evidence of Illyrian, Roman and Byzantine occupation sprinkled throughout the historic city, making Berat a fascinating crossroads of cultures and faiths.

The 15th-century Church of the Holy Trinity watches over the ancient city of Berat (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

The 15th-century Church of the Holy Trinity watches over the ancient city of Berat (Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Elton gave me a whistle-stop walking tour of the town, providing a superb overview of its history. Beginning from our hilltop accommodation – fittingly named Berat Castle Hotel – we weaved our way down the cobbled, sloping streets, stopping to admire the old town’s treasured landmarks. Its Byzantine chapels were filled with frescoes depicting religious figures, from John the Baptist to Saint Nicolas. During Albania’s lengthy period under Ottoman rule, several mosques were also constructed here. Sadly, only ruins now remain of the 15th-century Red Mosque, the oldest in Berat, which was designated a Cultural Monument of Albania in 1961.

Although the city is one of the country’s busier visitor spots, I was delighted to still see signs of local life and culture on its streets.

“The stone steps outside front doors are called prags, and locals would sit on them with a cup of coffee or raki and socialise with their neighbours,” Elton told me. “Older residents still do it, but usually in the mornings or evenings, when there are fewer tourists.”

The churches in Berat date back further than the Ottoman rule (Jessica Reid)

The churches in Berat date back further than the Ottoman rule (Jessica Reid)

When we finally reached the valley floor and stood alongside the ancient Osum River, I glanced back up to admire the architectural spectacle that gave Berat its nickname: ‘Town of a Thousand Windows’. It seemed a fitting symbol for a trip where instead of peering in from the outside, I’d been welcomed in and shown a more traditional glimpse of Albanian life. It certainly beat a day at the beach.

A few steps away, Elton gazed on quietly and it suddenly occurred to me: had he been the mysterious Mr ‘E’ of Eva’s prediction all along? I had taken in the length and breadth of Albania’s cultural heritage and natural wonders in the company of a kind, watchful stranger. If anything, it proved one indefatigable truth of life in Albania: never doubt the wisdom of the coffee granules.

Explore Albania’s protected natural areas

(Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

(Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Divjakë-Karavasta National Park in western Albania has a wildly diverse landscape of wetlands, coastal marshes and pine forests. It’s best known for being home to Karavasta Lagoon, the largest lagoon in Albania and a vital breeding ground for around 2% of the global population of Dalmatian pelicans. There are some 263 bird species within the park in total.

(Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

(Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Karaburun-Sazan National Marine Park encompasses a landscape of cliffs, caves and small beaches, and includes both the Karaburun Peninsula and Sazan Island in southern Albania. The marine park is home to flora and fauna such as loggerhead sea turtles, Mediterranean monk seals and seagrass meadows. More than 40 avian species have been recorded here.

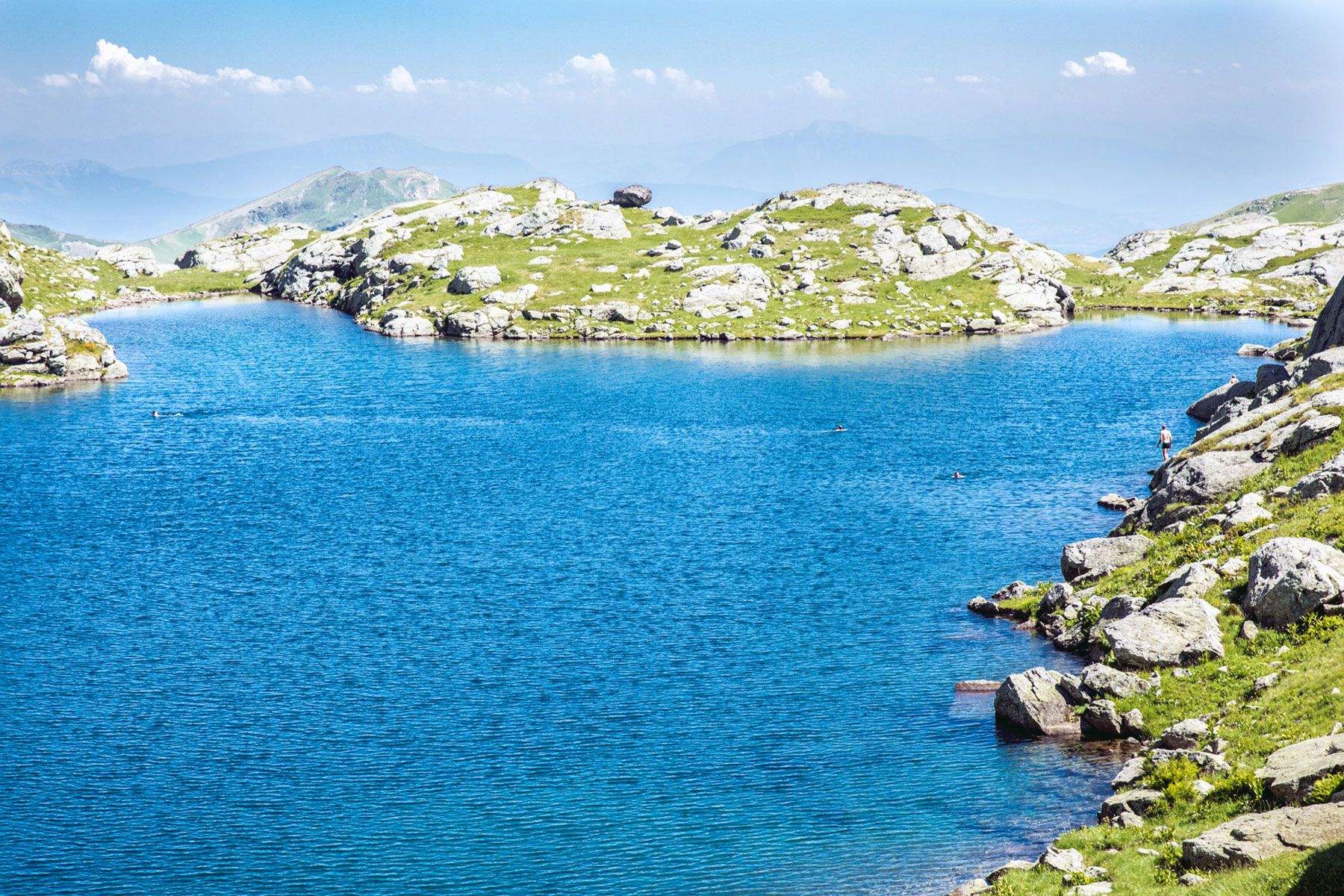

(Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

(Diana Jarvis/Intrepid Travel)

Thethi National Park is a 26.5 sq km site located within the Albanian Alps, near the border with Montenegro. Its diverse landscapes consist of steep mountains and beech forests, providing a habitat to brown bears, wolves and the elusive lynx. At its heart is the Shalë River, which flows into the waters of Komani Lake. It’s a glorious place for hiking.

(Shutterstock)

(Shutterstock)

Vjosa Wild River National Park was declared the first wild river park in Europe in 2023. The 272km free-flowing river is home to more than 1,000 species of animals and plants – some of which are critically threatened, such as the Balkan lynx. It flows from the Pindus Mountains in Greece to Albania’s Adriatic coast and is a popular spot for hiking and rafting.

About the trip

The author travelled with Intrepid Travel on part of its nine-day Albania Expedition, curated in partnership with the MEET Network*. The tour starts from £1,255pp, including eight nights’ accommodation, selected meals, activities and transport.

*The Mediterranean Experience of Eco Tourism (MEET) is a network of protected areas in the Mediterranean that works with tour operators to create low-impact eco-experiences that support conservation and local communities.