On 2 November, Mexico celebrates Día de los Muertos – commonly called Day of the Dead in the English-speaking world – to pay tribute to, remember and also welcome the spirits of the dead. Read our full guide to the celebrations here.

Celebrations take place all over Mexico, but there are a few regions where locals and visitors alike truly revel in the spirit of the holiday.

Here are the best places to celebrate Día de los Muertos in Mexico and beyond…

1. Oaxaca, Oaxaca

An Oaxaca cemetery on Day of the Dead (Shutterstock)

Celebrations in the city of Oaxaca last from 31 October to 2 November, and locals will often create symbolic altars, public art work and decorate their loved ones’ graves.

This ceremonial remembrance comes to a head at comparsas, a carnival-esque parade involving music, dancing and traditional costumes.

These carnivals aren’t strictly organised, and are scattered through the city streets. There’ll be plenty of visitors, as Oaxaca is often the go-to destination for travellers looking to experience Day of the Dead. Don’t just rock up, and expect a place to stay…

2. Pátzcuaro, Michoacán

Catrinas in Michoacán, Mexico (Shutterstock)

This town in the Mexican state of Michoacán has long been touted as one of the best places in Mexico to experience Dia de los Muertos.

Set on the eerie Lake Pátzcuaro, locals celebrate the Night of the Dead on the evening of 1 November in cemeteries with their loved ones, lighting up the graveyards with candles and tributes. There are even contests for the most elaborately decorated altar.

Offerings can also include the slightly-sweet pan de muerto (bread of the dead), as well as photos of the dear departed, which is said to draw out their spirits.

3. Janitzio, Michoacán

The island of Janitzio, Mexico (Shutterstock)

Also in the state of Michoacán is Janitzio: a small island off Lake Pátzcuaro. Home to a reported 1,600 people, Janitzio expands to welcome tens of thousands of visitors for Dia de los Muertos celebrations. Not just from Mexico, but the US, and all over the world.

Like its neighbour, cemeteries come to life with people, candlelight, and sugar skull decorations. At night, fishermen perform a butterfly dance from their canoes on the lake – the wings said to attract the souls of the dead. During the day, an open theatre on the island offers the chance to watch traditional Mexican dances, one of which is amusingly-titled Pescado Blanco (White Fish).

On 1 November, Kejtzitakua Zapicheri (the wake of little angels) takes place: grieving mothers and siblings leave sweets and wooden toys at the graves of their lost children, and hold a special ceremony to remember them.

4. Mexico City

Mexico City’s colourful Day of the Dead parade (Shutterstock)

The capital’s Día de los Muertos celebrations last three days. Its newest offering is a brightly-coloured parade throughout the city – costumes, lights, floats and live music all to be expected. It has different theme each year.

Admittedly, the parade is only three years old, partially because its aimed at visitors from other countries, who hope to witness the celebrations for themselves. It is the carnival-esque fanfare you’d expect, a real celebration – a great introduction to Día de los Muertos for the uninitiated.

5. San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, Oaxaca

A traditional floral tribute made for Day of the Dead (Shutterstock)

Tuxtepec is a small village in the state of Oaxaca. Here, you can expect the same bold, floral and traditional tributes to the deceased as you can in any of these Mexican destinations.

It does have a unique form of celebration, though; a rug-making contest. Rather than judge the handmade altars, locals spend the lead-up to Day of the Dead creating detailed sawdust rugs. They’re judged in the village square, until a winner is chosen.

Where to celebrate Day of the Dead outside of Mexcio…

6. Sumpango, Sacatepéquez, Guatemala

A colourful kite at Sumpango, Guatemala’s Kite Festival (Shutterstock)

A version of Día de los Muertos (often given a slightly different name), or the Day of All Souls, is celebrated throughout Central America. If not, the Day of All Saints on 1 November acts as an opportunity for communities to gather in cemeteries, decorate their altars, and remember their lost loved ones.

In Guatemala’s Sacatepéquez cemetery, Day of the Dead is marked with the All Saints Day Kite Festival, also known as Barriletes Gigantes. Locals and visitors alike design and create large kites out of natural materials – and when we say large, we’ve seen some 20m wide.

They’re often patterned or woven, but always bright and colourful – and flown high in the sky as a mark of respect. This practice has been happening for thousands of years, as many believe its a way of contacting the dead.

7. Tonacatepeque, El Salvador

El Salvador graveyard (Shutterstock)

There’s little point denying the intrinsic link between Día de los Muertos and its western equivalent, All Hallow’s Eve.

It takes place just two days earlier, and though Halloween is arguably far more about cool costumes and candy collection these days than it is about honouring the dead, its initial meaning – exactly that – is strikingly similar.

In El Salvador, the Calabiuza Festival, which takes place on the night of 1 November, is a rejection of Halloween-esque commercialism and more a local celebration of tradition. Residents of Tonacatepeque dress in costume, parade the streets, and celebrate their lost loved ones with music and dancing in the middle of town.

8. Fet Gede, Haiti

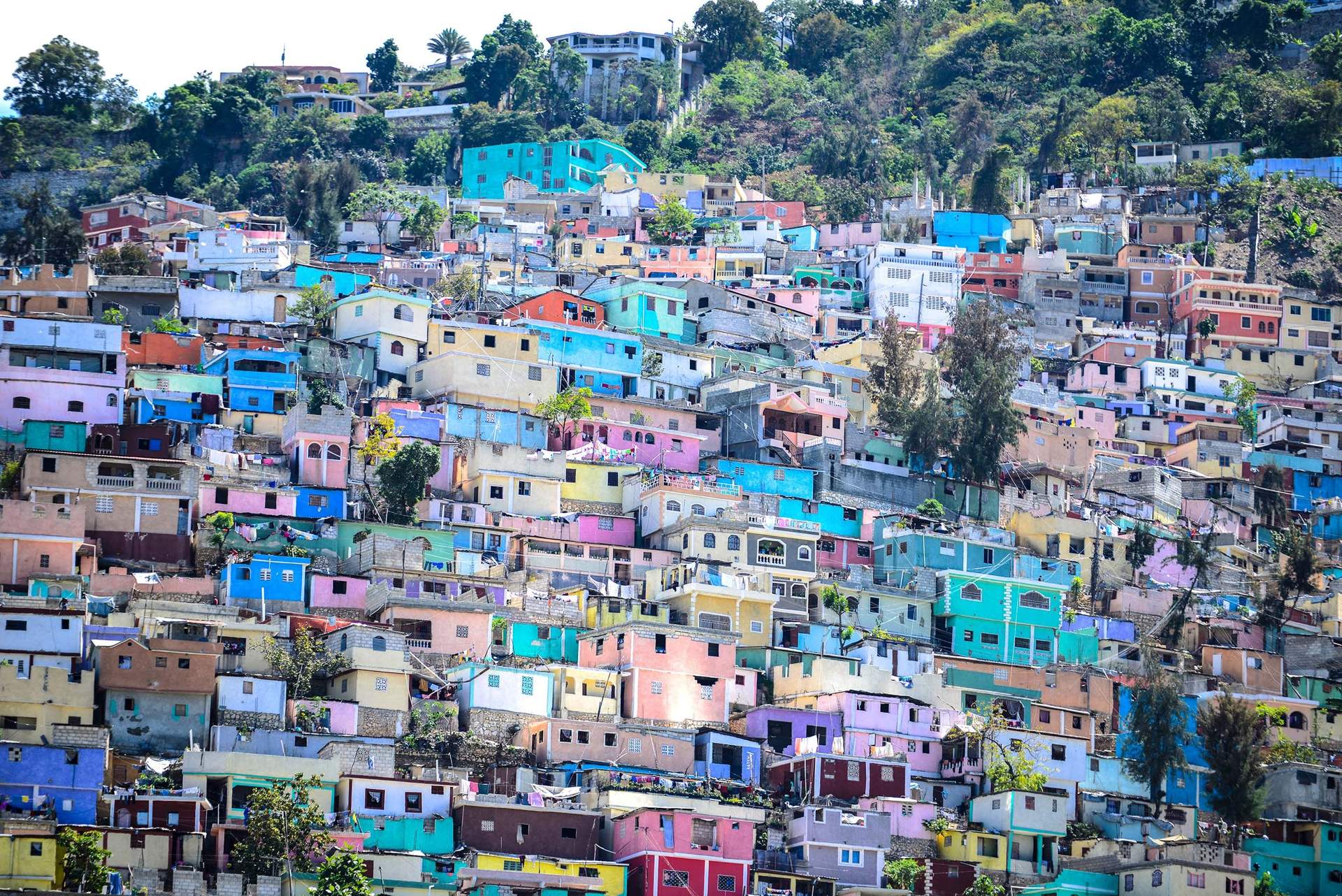

Port-au-Prince, Haiti (Shutterstock)

Fet Gede (sometimes called Fete Géde) is Haiti’s version of Day of the Dead. It pays tribute to Gede (or Guédé), patron family of the dead, in the religion of Haitian Vodou.

Like Día de los Muertos and its Central American counterparts, Fet Gede involves honouring the dead, creating decorative altars and cooking special dishes.

Particularly, there is a ritualistic element to Fet Gede: drum beats and dancing are part of the Vodou ceremony, done not simply to celebrate, but the movements are thought to help the souls of the no-longer living enter our realm.