The land without evil

Uncovering the history, culture and traditions of little-visited Paraguay

The ruins of Santísima Trinidad del Paraná mission

The ruins of Santísima Trinidad del Paraná mission

Paraguay has endured hard times over the centuries, yet the ruins of its Jesuit missions recall the days when its Indigenous people found a strange kind of paradise

Words & Photographs George Kipouros

“No journey in Paraguay can start without tereré,” smiled José Acosta Perez, my encyclopaedic guide, as he watched the street vendor meticulously select different herbs and then pound them together in a stone bowl. “It all starts with yerba maté,” he explained, pointing to a leafy green substance nestled among dozens of similar-looking herbs.

“Oh, the Argentinian drink,” I replied somewhat instinctively, causing him to visibly rumble in frustration.

A street vendor in Asunción prepares a cool glass of Paraguayan pick-me-up tereré, an infusion of yerba maté made with cold water, a lot of ice and pohá ñaná (a blend of Indigenous medicinal herbs)

A street vendor in Asunción prepares a cool glass of Paraguayan pick-me-up tereré, an infusion of yerba maté made with cold water, a lot of ice and pohá ñaná (a blend of Indigenous medicinal herbs)

“No, no, no! Yerba maté is originally from Paraguay; even its botanical name is Ilex paraguariensis. The local Guaraní people were drinking it as a herbal infusion long before the Argentinians claimed it as their own!” he declared while pressing yet another herb into my hand. “And this natural sweetener, stevia, is another one of our famous exports,” he smiled, taking in my bewilderment.

In truth, I knew very little about Paraguay, one of South America’s least visited countries, until arriving in capital Asunción. José was on a mission to give me a crash course on its history, culture and traditions before our road trip across the country’s southern region, where I would encounter its Christian Jesuit missions and their remarkable story.

The pinkish Palacio López is Paraguay’s present-day seat of Government

The pinkish Palacio López is Paraguay’s present-day seat of Government

Armed with our cooled tereré flasks, we began exploring the capital. Its historic downtown was full of imposing yet derelict colonial-era buildings that seemingly limped alongside the murky Paraguay river. I couldn’t help but think that it felt more like a quiet, provincial town than a major city.

“This is the small capital of a sparsely populated country; that’s why it feels so cosy,” José reassured. But it set me wondering. With just 600,000 citizens, Asunción is home to a respectable enough percentage of Paraguay’s 7 million-strong population, yet even that number seemed too small. This is no backwater; the country occupies a territory similar in size to that of Germany. It was at this moment that José seemingly read my thoughts.

“Ah, the perils of war have had a devastating impact on our land,” he intoned solemnly. We had stopped at the pink-hued Presidential Palacio de López, the city’s most prominent landmark. Named after General Francisco Solano López, it was completed just before the Paraguayan War (also known as the War of the Triple Alliance), which broke out in 1864.

“Unlike the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors, the Guaraní found the Christian missionaries a lot more amenable to their own worldview”

“We lost over 90% of the country’s male adult population during the war,” explained José. “We still haven’t recovered.”

It was a dark time in the country’s history. The war (1864-1870) was fought against the tripartite force of Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. It ended disastrously for Paraguay. As the losing party, it had to give up land to the victors, dramatically reducing its borders; but by then, its population had already been severely diminished and its economy devastated. The 20th century wasn’t much of an improvement either, marred by dictatorship and civil strife.

Asunción’s former Parliament building (Cabildo)

Asunción’s former Parliament building (Cabildo)

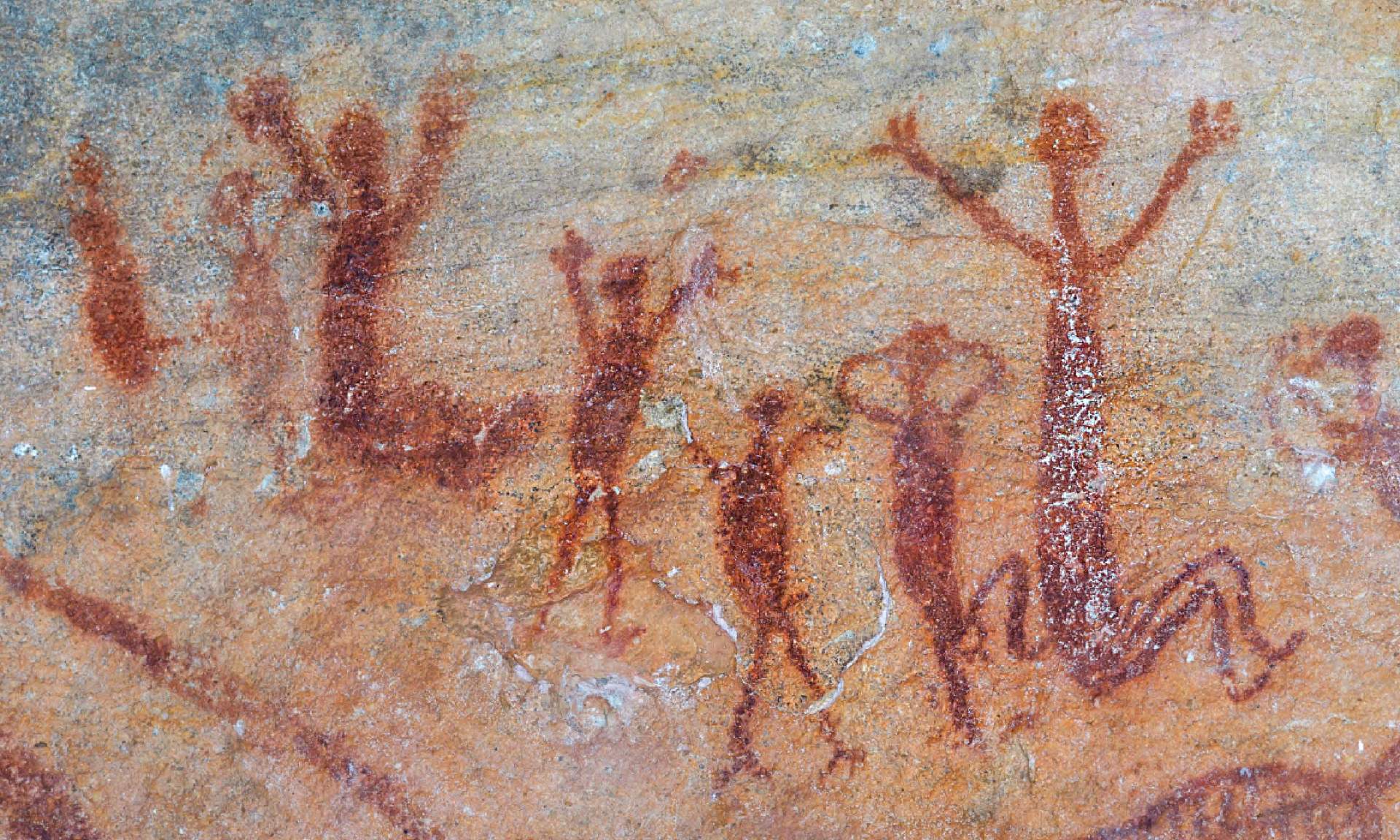

“The irony is that the local Guaraní people have always been peace-loving,” pondered José, describing their belief system as akin to a prophetic religion, focused on finding ‘Yvy Marãe’y’, or ‘a land without evil’.

José, like 90% of the population, spoke Guaraní, the unique Indigenous language that exists here alongside Spanish. Unlike the rest of the Americas, however, Paraguay is the only nation on the continent with an Indigenous dialect as its official national language.

“Modern-day Paraguay is a fusion of Guaraní traditions and Hispanic influences,” explained José, stoking my eagerness to learn more about the intersection of its Indigenous people and the Europeans. “It all started with the Catholic missionaries that first made contact with the Guaraní in the 16th century. But our story is quite different to that of our neighbouring nations.”

The Church of San Roque Gonzalez is named after the first missionary to visit the Guaraní people of Paraguay

The Church of San Roque Gonzalez is named after the first missionary to visit the Guaraní people of Paraguay

José had arranged a private visit to Asunción’s Museum of Sacred Art, whereupon director Luis Lataza took over. The narrative of modern Paraguay is closely linked with the arrival of its Catholic missionaries: first the Franciscans, then the Company of Jesus, known more commonly as the Jesuits.

“Unlike the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors, the Guaraní found the Christian missionaries a lot more amenable to their own worldview,” explained Luis.

Indeed, the Guaraní belief system shared many commonalities with Christianity’s biblical teachings, making the missionaries’ work here easier. It was something that became clear as we explored the museum’s religious works and their distinctly Baroque look.

“This is the Mestizo Hispano-Guaraní style that is unique to our country,” remarked Luis. Paraguay, as a nation state, did not exist when this style developed, and he explained how the Guaraní had adopted the Baroque European traditions of the time, filtering them through their own understanding. “The period of the Jesuits, in particular, ended up being a thriving time for the Guaraní, with the creation of vibrant, safe and highly creative settlements.”

Luis was talking of the reducciones (reductions), Guaraní-Christian missionary settlements, of which more than 30 were originally built in a region that is now split between Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil.

“Paraguay has arguably some of the best-preserved remains of these settlements,” continued Luis as he pointed to a map showing just how widespread the Jesuit missions had been. He concluded the tour by highlighting Guaraní-influenced religious artwork that had been salvaged from a number of the missions, and by encouraging me to visit “as many as I had time for”.

I was vaguely familiar with the story of the Jesuit missions in Paraguay, having watched the Palme d’Or-winning 1986 film The Mission with its – spoiler alert – brutal ending.

“The film is surprisingly historically accurate,” agreed José while countering that its locations are mostly fictitious, particularly in relation to Iguazu Falls. Instead, he showed me a road-trip route that took in some of the most important religious monuments of the country, branded by Paraguay’s tourism board as ‘the Jesuit Route’.

The Franciscans built some of the region’s first Catholic institutions, and their San Buenaventura de Yaguarón church remains remarkably intact

The Franciscans built some of the region’s first Catholic institutions, and their San Buenaventura de Yaguarón church remains remarkably intact

After less than an hour’s drive from Asunción, we arrived at Yaguarón to visit the town’s show-stopping centrepiece: the only intact church in Paraguay that comes from an original Christian missionary reduccione, albeit one built by the Franciscans. However, its style was later mirrored by the Jesuits in their own settlements.

The simple white limestone and timber exterior did not prepare me for the ornate gilded interior: an explosion of Baroque maximalism with subtle Indigenous references.

Surprisingly, there were no other visitors in the church – a pattern mostly mirrored throughout my travels across Paraguay.

Inside Yaguaron church

Inside Yaguaron church

“We used to have many more visitors when Paraguay was the gateway to Iguazu Falls,” acknowledged José. The country has indeed witnessed a steady decline in visitor numbers over the last two decades, and still very much feels unspoilt by tourism compared to many of its South American neighbours.

The mellow, harp-heavy rhythms of the Paraguayan polka provided a suitable soundtrack to the evergreen, lush fields we passed as we drove further south. Much of this region is planted with yerba maté, I was told.

“Our land is so fertile that we can have three different crops a year,” smiled José, “and that is what makes our beef so tasty.” Paraguay is one of the world’s leading exporters of beef, and we passed by thousands of cows, some of them seemingly free-range.

Fittingly, we also encountered many arrieros (Paraguayan cowboys), who waved hello with their hats every time we passed them by.

A group of arrieros (cowboys) trot past

A group of arrieros (cowboys) trot past

We made an overnight stop in Santa Maria de Fe, where local guide Lelis opened the town’s museum for us, which was run from a traditional Guaraní house that had been restored in 1980. The town’s namesake Jesuit church burned down in 1889, but thankfully many of the altarpieces and statues were saved. These are still used in modern-day rituals within the community, especially during local religious festivals.

The Santa Maria de Fe church was built to replace the old Jesuit one that burned down in 1889

The Santa Maria de Fe church was built to replace the old Jesuit one that burned down in 1889

“Christianity, Catholicism are still central to Paraguayan identity; we are quite religious people,” affirmed Lelis as she showed me some of the original Jesuit statues, now repositioned in Santa Maria de Fe’s new church.

It was a full house when I visited the fully restored church of the San Cosme y San Damián mission on a Saturday morning. Interestingly, it was the city’s youths that made up most of the worshippers. Augustin, my Guaraní guide, explained that regular workshops and many activities for the town’s residents were still run on the site and that it didn’t just operate as a museum.

Having originally been founded in 1632 with some 3,000 Guaraní, I was surprised to learn that the settlement of San Cosme y San Damián had a reputation among the Jesuit missions for its scientific achievements.

Augustin shows off the sundial in the courtyard of San Cosme y San Damián

Augustin shows off the sundial in the courtyard of San Cosme y San Damián

“Somehow we managed to become the main centre for astronomy in South America,” beamed Augustin. Central to this was the work of Father Buenaventura Suárez, a scientist and geographer who worked with the local Guaraní in the early 18th century, building telescopes, a pendulum clock, an astronomical dial, and a sundial that still stands in the restored site’s courtyard.

San Cosme y San Damián, which was founded in 1632 by Father Adriano Formoso, still has a functional church, after it was restored upon the request of the local community

San Cosme y San Damián, which was founded in 1632 by Father Adriano Formoso, still has a functional church, after it was restored upon the request of the local community

I bid farewell and moved on to the UNESCO-listed Santísima Trinidad del Paraná, which is probably the most captivating of all the eight surviving Jesuit mission sites in Paraguay. With grandiose ruins set amid tropical vegetation and towering palm trees, it resembled a Christian version of Angkor Wat. Trinidad is indicative of the typical scale of the Jesuit missions, featuring a large main plaza surrounded by an imposing church, a school, artists’ workshops, multiple houses and a cemetery. Overall, the atmospheric state of Trinidad’s ruins made it feel much older than its 1706 foundation date.

Trinidad by night

Trinidad by night

Visiting the main church, we discovered Baroque, Romanesque, Greek and Roman influences, all infused with local Guaraní elements. In this unprecedented acculturation process, the Guaraní were never forced to fully ‘Europeanise’, and their culture and traditions were incorporated in Jesuit Catholic teachings. In turn, the Jesuits shared their knowledge of the arts, music and their technical skills with the Guaraní, who readily adopted and evolved these teachings.

“With its grandiose ruins, the Trinidad mission resembled a Christian version of Angkor Wat”

“The Guaraní liked the Jesuits because, like them, they lived very simple lives; their clothes were not fancy and they worked hard together,” explained José, elaborating the social structures of the day. “They ultimately became close with the Jesuits, considering them their equals; their brothers, who suffered or prospered alongside them,” he continued, comparing this with the damning treatment of Indigenous populations in the Americas by the Spanish and Portuguese.

“Plato’s The Republic and Thomas More’s Utopia were reportedly taking place in Paraguay,” chuckled José, referring to surviving documentation from the Spanish and Portuguese authorities, which expressed surprise at this unique example of a colonial missionary expansion.

For many Guaraní, this was finally their ‘Yvy Marãe’y’; their land without evil. However, all good things must come to an end, as my next destination reminded me.

The Jesús de Tavarangüe Jesuit Guaraní mission was the last stop on our road trip, a mere 20 minutes’ drive from Trinidad and also part of UNESCO’s World Heritage list. Set amid lush, hilly landscapes, the remains of a monumental church still dominate the site. If Trinidad looked like a Christian Angkor, then Jesús could have been Borobudur.

The Mudéjar-style arches of the interior of the unfinished church at Jesús de Tavarangüe recall designs found in Moorish Spain

The Mudéjar-style arches of the interior of the unfinished church at Jesús de Tavarangüe recall designs found in Moorish Spain

“The church at Jesús would have been one of the largest in South America were it to have been finished,” related José as we walked around its columnated interior. Its architectural style couldn’t feel more out of place with the surrounding jungle, with its strong Mudéjar (Christian-Arab) influences almost reminiscent of Andalucía.

This church and site comes alive in the evening when a 3D projection narrates the story of the Jesuit missions in Paraguay. I was one of a handful attendees escorted back into the site at sundown by local Guaraní guide Kuaray, who was dressed in Jesuit-inspired attire. The video projected onto the walls of the unfinished cathedral was equal parts stimulating, patriotic and heartbreaking as it came to its end – and that of the Jesuits.

The story of the Jesuits is projected across the church walls at the Jesús mission

The story of the Jesuits is projected across the church walls at the Jesús mission

The economic growth of the Jesuit missions and their continued political independence caused animosity among the Spanish conquistadors, who ravaged the neighbouring regions. There were multiple attempts to bring the missions back under the complete control of the Spanish authorities. The dramatic ending to this utopian experiment came when the Jesuits were expelled from the Americas by decree of the King of Spain in 1767, bringing a forced end to the missions and evicting an estimated 100,000 Indigenous inhabitants. The church at Jesús was never to be completed and the site was abandoned.

Was it really a utopia that existed here during the time of the missionaries, I asked Kuaray, eager to understand how history had imprinted itself on the local psyche?

“Becoming Christian meant that the Spanish could not readily kill us, as if we were non-believer natives,” he explained with a pragmatism that was all too understandable. Being part of the reducciones also meant the Guaraní were protected from European slave traders as well as the Spanish encomienda, a colonial forced labour system with heavy overtones of slavery.

“Christianity was as much a necessity for the local population as it was a choice,” Kuaray concluded.

As we departed the site for our return to Asunción, I asked José what he thought of the Guaraní prophecy of a ‘land without evil’.

“Perhaps it’s not as distant a land as it sounds,” he affirmed with a curious smile. “In Paraguay we already have fertile land, great weather, wonderful people. Perhaps our promised land has been here all along.”

About the trip:

The author’s ground travel was organised by Journey Latin America.

A seven-day tailor-made journey following the same route, including Asunción and the Jesuit missions, includes hotels on a B&B basis, excursions and transfers.

Accommodation:

Asunción has a number of good hotels, including the Jesuit mission-themed La Misión Hotel Boutique.

Outside of Asunción, accommodation and restaurants are in short supply and are of low quality. Hotel Papillion, located close to both Santísima Trinidad del Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangüe, is a notable exception and a good base for visiting the missions.