Interview

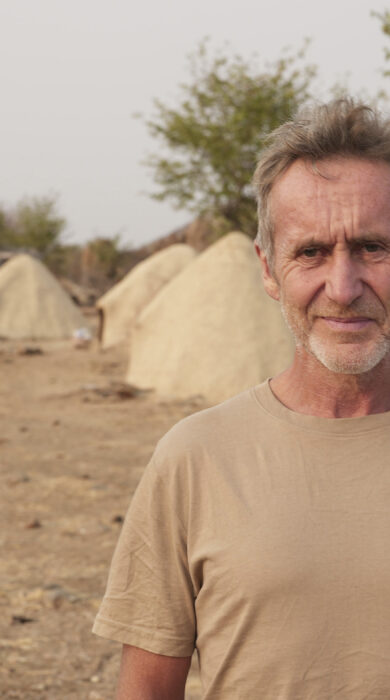

Interview: Bruce Parry chats Tribe’s reboot, the changes since it first aired and what’s next

More than 20 years after it first aired, Parry explores the impact of climate change and the wider modern world on Indigenous ways of life

It’s been many years since Tribe was on our screens… how did the new series come about?

I left the BBC 15 years ago, but I was still in communication with them, and just before COVID I was going to do a new series of revisiting the Amazon but we pulled the plug on that because of the situation. So I was already in conversation with them about how I would come back, and would it be something that we both wanted? And then Charlotte Moore, who was the head of programmes suggested, why not do Tribe again, and I jumped at [the opportunity].

So what have you been doing in the meanwhile?

It took me 10 years to make a feature film, Tawai: A voice from the forest, and I made pretty much every mistake a first time director makes, and it was just a long old journey. But in the making of that, I left Spain where I was living. I moved to Wales, where I lived for about six or seven years, and I just sort of hung up my boots for a while.

When this came along I decided to shift again. So I’ve left Wales, and I’m now back on the road in a way.

So having decided to bring Tribe back, what were the next steps?

The world’s changed a lot since we made those first series. And one thing that’s happened is that Tribe being the success that it was spawned a whole new generation of TV programs in Indigenous spaces. So it was quite hard to discern where to go, and find what things interested me, and things that would interest the audience, and were acceptable and affordable. So there’s a big team effort. And we’ve always had teams of researchers and they scoured the world in the way that we always have, talking to anthropologists, talking to whoever it is to see.

The first episode is in the Amazon, albeit the Colombian Amazon, but did that feel like being back in familiar territory?

Yes, that episode, more than any of the others, felt very much like the Tribe of old. And it was an area that I really wanted to go to. They’ve been on my radar for a while, as people who have a very strong plant medicine tradition, and also have a very strong desire to to really fight for the forest. And so they don’t let a lot of people in. It’s quite a hard place to get to anyway, because of cataracts in the rivers and the waterfalls are too high to transit. So it’s quite hard to get there from Colombia.

Obviously, I’d spent a lot of time in the Amazon over the years, and it felt very much like I’m back.

Were there differences in what you encountered?

Yes, for sure. Tribal groups have changed throughout the world. The encroachment of modernity in all of its forms is everywhere, so most alarming is the increasing stress on the resources. The miners and the loggers and the missionaries, and all of these people, are the main forces that are affecting change, and that’s just accelerated over time. The Amazon is the place that everyone knows about being affected but it’s the same everywhere.

And also interconnectivity technology. People have mobile phones. People have access to places where they can get online. So that’s changed a great deal.

And are there any differences within yourself?

I’ve changed, in that, since I made Tribe, I’ve made lots of other programmes and I’ve travelled much more. And I’ve been involved in these sorts of conversations. You know, it’s 15 years since I did television, so I’m coming to it as a more mature and more knowledgeable person. I’m also older, so not as physically adept as I was.

Audiences have changed, because in the interim we’ve had much greater public awareness of colonialism, neo-colonialism, of cultural appropriation, of gender and sex issues, and a hundred other things, as well as a lot more television on Indigenous peoples. So they have changed and also the tribes have changed. So basically, everything has shifted.

There’s still something very beautiful to be found, and something very clean and clear and precise in why Indigenous peoples are still very different, and living very different lives to the way we do. And that’s what we’re there investigating and enjoying learning about. So there’s definitely still a reason to go. And there’s definitely lots that is there for us to learn, but there’s no doubt that the changes are everywhere.

The second programme featured the Mucubal of Angola. How did you choose Angola as a destination?

Understandably, there’s not been a lot of tourism there because of the Civil War and so, it just felt like a real sort of journey into somewhere that many people don’t know much about, and that was as much as anything, a good enough reason to go.

We see in that episode, of course, the impact of climate change beginning to take effect.

I think climate change is affecting all peoples everywhere, and the people who are closer to the land, which is what Indigenous peoples are by almost by definition, are much more aware of it in some places. And so for the Mucubal, they’ve always been used to living in an arid area, but the length of the droughts is getting longer, the intensity of the heat is increasing, and for them it’s therefore a much more visceral experience.

The three places and communities were very different, but do you see similarities in Indigenous communities around the world?

It’s very hard to define what an Indigenous community is. Even the IMF, the World Bank and the United Nations all have subtly different definitions. But there are certain traits that are very real and one of them is this connection to the land, the continuing cultural relationship with a place, and a group of people who define themselves as different from the host nation state.

But the commonalities are very real, in that they live much more communally and much more locally. By and large, they’re still living from their immediate surroundings, and as a result, are much more aware of their impact on the immediate surroundings. And that’s why they are very often advocates for the land, because they can see the impact humans have in the way they live. They see their own impact and then are also feeling very strongly the impact of the rest of us who don’t experience our impact.

So they’re very often strong advocates for land stewardship and nature relations. And you look at the statistics that come out of places like the Amazon, where 80% of intact land is in the hands of Indigenous peoples, and everything that’s not being held by them is being ransacked and ravaged by us.

So yes, there’s lots of things that they have in common. Many of the groups have had a shift in their belief systems dependent on how many missionaries have been knocking on their door. But in living memory, there’s very often a nature-based spiritual tradition, and even if they’ve become Christian or Muslim, they still very often carry on a nature-based spiritual belief system as well.

That was particularly true in the third episode, in Sumba. The Marapu group that you stayed with are living amongst the spirits of their ancestors. Did that surprise you?

No, no, it’s beautiful. The tombs are right outside the front of the house, but it’s very common for Indigenous peoples to have a strong relationship with their ancestors. That’s not unusual, but it was a defining aspect of that particular culture. And what was really nice is that, unlike many of the Abrahamic traditions where the spirits go into heaven, which is basically in the sky, you find for many Indigenous peoples that the spirit world, and where the ancestors dwell, is actually very local. And for the Marapu, of course, it’s right in the village.

And that is a subtle but profound difference in the way that we perceive the afterlife. For them, the afterlife is part of the living community, and they’re both living in their different ways. The continuation of life is part of those who remember you. And they remember you because almost every cultural ritual includes the ancestors, and they’re spoken to as if they’re still there. And, more importantly, it’s not just a one-way ticket whereby the living, as we see them, are remembering the ancestors. And isn’t that lovely, that you’re being remembered? They also see that they need the ancestors, the ancestors are protecting them.

And so it’s actually a two-way thing. They remember them, but also the ancestors are helping them – so it’s a much stronger connection. As a result, it’s not you’re dead and we’ll remember you as a kind of act of kindness. It’s more like, no, no, you’re really important to us. And that highlights the importance and the connection, but it also renders it really vital for every member of the community to die and be buried back home. You can disappear off to go and earn your money elsewhere but you must find your way home to die. And actually, there’s a there’s a huge fund in Sumba itself to bring those people who die abroad home because it’s actually part of the whole island’s traditional belief system.

You seemed particularly moved when you were saying goodbye to the Marapu.

As you heard, they called me a peanut without a shell. And they were referring to me, but also to our culture and that was really beautiful. It wasn’t the first time I’ve come across it, but it was directly placed at my feet. But I think my tears in that moment were because I had a really beautiful time with that group, and it’s always difficult to say goodbye. I just let myself go a little bit more on that particular occasion.

What else are you working on?

I’m writing a book which is a much deeper look at all of my tribal experiences, and I’m also looking to get a feature doc off the ground at some point, too, about my Indigenous insights. And one or two in particular, especially around egalitarianism and our deep ancestry, that I feel that people really could benefit from hearing about.

The final episode of Tribe with Bruce Parry is on BBC2 this Sunday, 13 April. All three episodes are available now on BBC iPlayer